A Lantern for Jack, the Hallow!

or: What is the difference between „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“ and why all Jack O’Lanterns are orange?

Dear Jack O‘!

You are dead now, wandering with the Manitous. We light a candle in place of your brain as a reminder of the sun and her reflection on earth, the fires which made our brain once growin‘.

Amen!

I am standing here at your grave to tell the people the story of your life.

Cucurbit for carving a Jack O’Lantern

I want to tell’em, that in the beginning you were a „Squash“ and nourished people for thousands of years jointly with your companion gods „Corn“ and „Bean“.

Then, I want to tell how you became a pumpkin and had to feed livestock.

I’m going to talk about your cousins in the southern parts of the Americas.

I will complain that you and your cousins are filling our marketplaces and supermarkets in so many shapes and colors today, that many folks went crazy and don’t know your names anymore (one of them was me).

The last part of the story is how you became a hallow and a symbol with the skin color of your first keepers.

It took me a long hike through history to see more clearly, but here comes the truth…

In the 1st chapter, I give reasons for why I wanted to know the difference between „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“

Once, I didn’t know much about you, Jack O’Lantern, besides that everybody calls you „Pumpkin“. I didn’t ask questions.

But when I was writing an article about the beginning of human plantculture, I remembered a description of hoe-farming in a book which I have in my bookshelf since I was a student, George Catlin’s „Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians“ from 1843.

This U.S. American painter had visited the Native people at the upper Missouri in 1832 and had noticed: „The Mandans are somewhat of agriculturists, as they raise a great deal of corn and some pumpkins and squashes“ (p. 121).

The German translator of Catlin’s book in 1848 didn’t ask for the meaning of squashes and pumpkins and just translated both as cucurbits („Kürbisse“, p. 89).

Basically he was right, squashes and pumpkins are both cucurbits, but I wanted to know the difference. If a non-specialist like a painter could distinguish squashes and pumpkins, they must have obvious differences.

O, Jack, it has been a long road to discover all your secrets!

In the 2nd chapter, I explain the origin of the word „Squash“ and what it means

After a hint by an archeologist I learned, that „Squash“ was your first name, given to you by native North American people, the Narragansett, an Algonquian speaking group living in the region later called „New England“ and the South-East of Canada.

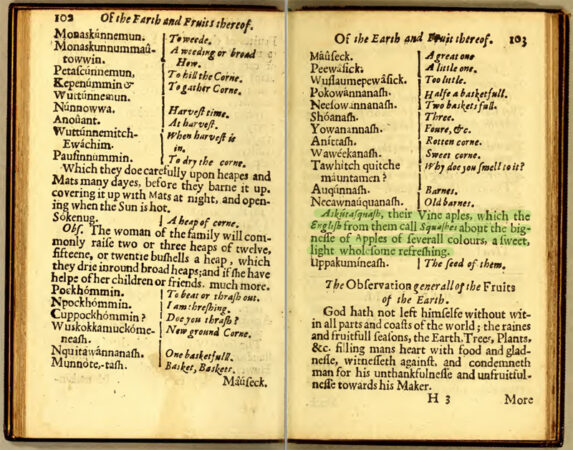

„Askútasquash“ is the original version that Roger William reported in 1643; he explains that you were „their Vine aples, which the English from them called Squashes about the bignesse of Apples of severall colours, a sweet, light wholesame refreshing.“

Descreption of „Askútasquash“ in „The Key into the Language of America„

Modern Etymologists have the opinion that the word means literally „things that may be eaten raw,“ from Askùn „green, raw, uncooked“ + asquash „eaten“, in which the -ash is a plural affix.

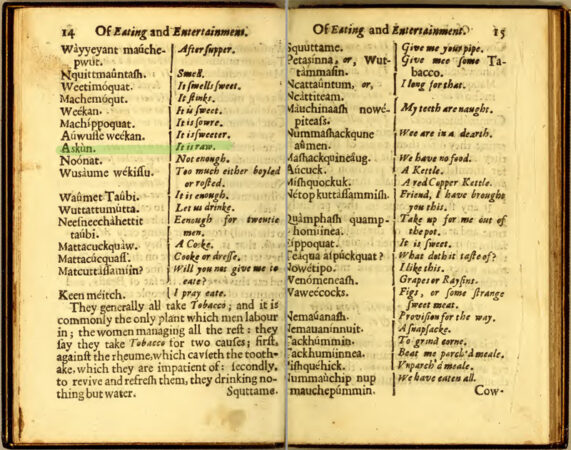

The word „Askùn“ on page 14 in „A Key into the language of America“ by Roger Williams

I think they are wrong; „raw“ does not mean „uncooked“ but „unripe“ („uncooked by the sun“), because you were never eaten raw, Jack O‘, you always were cooked by humans before eaten.

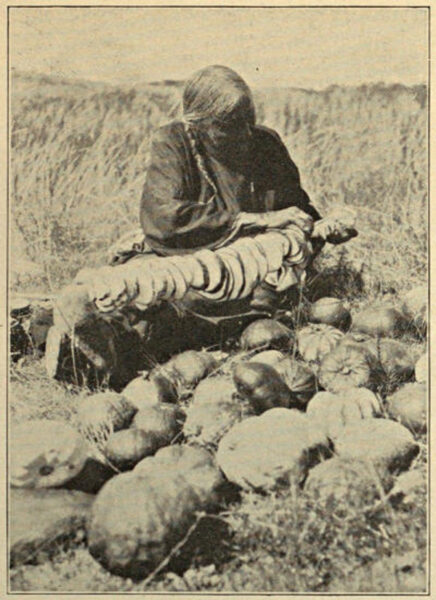

Listen to the words of Buffalobird-woman, a indigenous Hidatsa.

The Hidatsa were relatives of the Mandans, which Catlin had visited. They were nearly exterminated by Smallpox a few years after his visit, …not more than 150 persons surviving. The same epidemic reduced the Hidatsas to about 500 persons., G. L. Wilson wrote in the foreword of his very informative book „Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians – An Indian Interpretation“, published in 1916, I will read of a little bit for you in the next lines…

In the section about SQUASHES Buffalobird-woman tells us: The first squashes of the season that we plucked were about three inches in diameter [around 7,5 cm]; that is, they were gathered as soon as we thought they were fit for cooking; […]

There might be three or four basketfuls of squashes at this first picking. These squashes we did not dry, but ate fresh; as they were the first vegetables of the season, we were eager to eat them.“

Squashes, the first fresh vegetable of the year, were cooked young and unripe, but mostly they were dried and stored in this stage.

Some of the squashes were used as seed squashes and then harvested and stored in ripe stage.

These ripe squashes were also eaten, as were the seeds (Buffalobird-woman: I was rather fond of squash seeds“).

Cooking the Ripe Squashes

When now we wanted to have squash for a meal, I went over to this heap of ripe seed squashes and brought a number over near the fire. There I broke them open, carefully saving the seeds. I would lay a squash on the floor of the lodge; with an elk horn scraper I would strike the squash smart blows on the side, splitting it open.

The broken half rinds I piled up one above another, concave side down, until ready to put them in the pot. Ripe squashes were less delicate than green four-days-old squashes, and did not spoil so quickly.

If the American Natives gave you other names when you grew up and ripen, Jack O‘, I don’t know; but there were hundreds of languages and dialects in the Northern part of the Americas and there must have been hundreds of names for you; but you always were eaten by people and so, one name was enough: „Squash“, although There was a good deal of variety in our squashes. Some were round, some rather elongated, some had a flattened end; some were dark, some nearly white, some spotted; some had a purple, or yellow top.

„Squash“ is a rare exception that Europeans adapted words of Indigenous people for unknown things. They preferred more to use their own words – like „Pumpkin“…

In the 3rd chapter, you hear about the origin of the word „Pumpkin“ and what it means

The root of „Pumpkin“ is the Ancient Greek word πέπτω (péptō) which means “ripen” and „πέπων“ (pépōn) which means „ripe“.

Primarily, in the „Old World“ this word was used for ripe melons, cucumbers or calabashes. These fruit were often big, swollen and inflated when ripe.

When the „New World“ was discovered by Europeans, the more pompous (!), ripe fruit of you, Jack O‘, and your brothers and sisters fall under this term either. It didn’t matter if the fruit was oval or round, it just had to be big and ripe to be called „pepo“ by Latin speaking Europeans.

Over Latin „pepō“, Middle French „pompon“, the old English form „pompion/pumpion“ the ancient Greek word became at last „Pumpkin“.

Poor Jack O‘, when the white man came into your country you got two names and the confusion began…

In the 4th chapter, I tell you my first step to an answer and how the Europeans made a difference between squashes and pumpkins

After I had presented the question „What is the difference between squash and pumpkin?“ to modern search-engines without getting much valuable information, I had to think myself of other ways to find an answer.

What about old seed catalogues (before 1910)? Did they make a difference between „Pumpkin“ and „Squash“?

Yes, they did! The very most had extra sections for seeds of pumpkins and squashes.

Studying these antique seed catalogues I found:

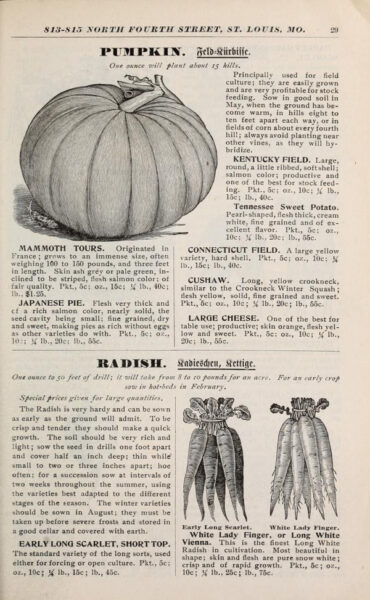

Pumpkin: „Principally used for field culture; […] Sow in good soil in May […] in hills eight to ten feet apart each way, or in fields of corn about every fourth hill…“

Squash: „The squash is one of the most nutritious and valuable of all our garden vegetables […] Plant in well manured hills, […], the bush varieties three or four feet apart each way, and the running kinds from six to eight feet apart…“

In some of these catalogues, in the section for pumpkins I found the German word „Feld-Kürbis“, what does mean „field cucurbit“; on the other side C. pepo in German is called „Garten-Kürbis“, what is identical to „garden cucurbit“.

Page of „Descriptive catalogue of Schisler-Corneli seed company“, 1898

So, I made one step ahead: Pumpkins were grown in those days by the small scale farmers of the time, still based on selfsufficiency, in fields, together with corn/maize and beans like the Indigenous did/had done; in Mexico this mixture of plants was called „Milpa“ and in northern parts of America it was called „Three Sisters“ by the Iroquois.

Pumpkins could only be harvested when all plants (corn, bean and cucurbit) had ripe fruit. So pumpkins were used when ripe.

These ripe cucurbits were often used as fodder for livestock in winter because they could be stored well. But they were also eaten by the farmers themselves in winter in lack of fresh vegetables (e. g. as pumpkin pie).

All pumpkins had indeterminate growing vines; they needed more space than squashes between singular planting spots as you may see in the planting recommendations by the seed companies.

Squashes, on the other hand, had bushy habit or terminated shoots and were grown in gardens preferable for human consumption in unripe stage. They were harvested and eaten fresh in summer but surely also ripe as the Indigenous did.

The most small scale farmers in the 19th century will have used their own seeds just like Buffalobird-woman had told.

At that time, Jack O’Lantern, you would have been a pumpkin, without any doubts – but you wouldn’t have become a lantern, you would have been eaten by poor farmers, cows and pigs…

…but the distinction between squashes and pumpkins were clearly recognizable even for a painter as garden cucurbits (squashes) and field cucurbits (pumpkins).

In the 5th chapter, I introduce Jack O’Lantern’s cousins from the southern parts of the American continent and make some remarks on the intercourse between cucurbits

Thousand of years, Jack O‘, you were alone with the original human inhabitants of your country. You were not really alone because you had hundreds of brothers and sisters in different shapes and colors in the North, like Buffalobird-woman had told us above.

But the Europeans traveled farther and discovered more distant countries and more members of your clan. They found cousins of you in the tropical parts of the Americas and in the Southern hemisphere of this continent, they often called „Pumpion/Pumpkin“ as well.

Scientists debated a long time about their naming because the classification in „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“ wasn’t suitable anymore. At the end they agreed on a system of two names based on your clan’s name (also called „genus“) „Cucurbita“ and your family’s name (also called „species“); so, you got the new name „Cucurbita pepo“.

Below I have compiled a list of most of your clan members, arranged by their birthplaces from north to south, so, that your name comes first:

- „Cucurbita pepo“, you, Jack O‘, your brothers and sisters, grew up in the North of the American continent (north of Chiapas in Mexico) and was named by Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus in 1753.

- „Cucurbita argyrosperma“, better known under its name „Cushaw“, was domesticated by native Americans in Northern Mexiko. Many years scientists believed that it would be the same as the following clan member „Cucurbita moschata“ because of many similarities. This species is of lesser interest.

- „Cucurbita moschata“ was domesticated by the Natives of Meso-America, in the tropical regions of the continent, and given its name by French botanist Nicolas Antoine Duchesne in 1786.

- „Cucurbita maxima“, also named by Duchesne, is a species from the southern hemisphere, south of the equator, used by Natives which lived in the modern states of Brazil (in the south), Argentine, Uruguay, Paraguay and Chile.

How do you like that, Jack O‘?

On the following graphic the centers of „domestication“ of your whole clan are marked by colored circles.

Hypothesized origins of domestication for the Cucurbita species are indicated by open circles.

Your cousins‘ families also had hundreds of members of different shapes and colors, with trailing vines and bushy growth.

I know you were looking forward to having more alternatives in sex and being able to mingle with this motley crowd, but you had to learn that you can’t.

No, no, there were no moral restrictions! You could have intercourse with your cousins but no fertile children…

For all non-believers, 1929 botanist L. H. Bailey wrote about this fact in Gentes Herbarum (p. 70):

In the work with cucurbits, there were numbers of attempts to combine the three species C. pepo, C. maxima and C. moschata. It was a common notion with gardeners that these three species intercross interminably. All efforts to combine the three species have failed, and I became convinced that under common garden conditions none of these species habitually hybridizes.

In the 6th chapter, I show how Jack O’Lantern’s clan made marketing impossible and the use of „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“ confusing

After immigration of lots of your clan’s families to the North in the 19th century, merchants and seedsmen had a hard time sorting them all correctly into the usual categories „squash“ and „pumpkin“.

Since many of these new immigrants shared the same obvious characteristics as you, Jack O‘, large fruit, running vines, and were growing in fields, they had to be called „Pumpkins“, but a lot of them were much tastier when ripe, than you.

While small farmers had no problem eating a better-tasting pumpkin, merchants couldn’t sell pumpkins to wealthy customers, because pumpkins had the odor of fodder and poor man’s food.

Something had to happen. One solution would have been: Commute good tasting pumpkins into squashes.

I modify a statement of two scientists from Iowa in 1927, we will hear more about in a minute: Retailers, seedsmen and growers wanted any variety of merit for table use as a vegetable to be called a squash regardless of its place of planting, plant habit, or its botanical relationship. But it is a fact that baked pumpkin is quite palatable as baked squash.

These facts made the idea of a simple metamorphosis impossible.

But the first director of the New York Agriculture Experiment station, E. L. Sturtevant, had given a hint for a solution before his death in 1893: The word „squash“ […] seems to have been originally applied to the summer squash.

You get it, Jack O‘?

Yep, in those days the interested groups invented the winter squash!

Winter squashes? Winter squashes! Spaghetti squash (C. pepo) and „Sombra“ a blue variety of C. maxima

Since then, Jack O‘, cucurbits eaten unripe are called „Summer Squash“. Tasty Cucurbits which were eaten ripe, are called „Winter Squash“, and the whole rest is called „Pumpkin“ (or ornamental, bitter tasting „Gourd“) without regard of the membership to one of the species in the genus Cucurbita listed above.

We may resume: There wasn’t a difference between „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“ anymore, because everybody could name cucurbits by his own ideas.

Merchants, seedsmen and growers were happy with that, but you, Jack O’Lantern, you became a second-class cucurbit. But your time will come…

In the 7th chapter, I present an attempt of scientists to resolve the confusion that has only made matters worse

…but scientists wanted it more precise.

The above mentioned scientists from the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, E. F. Castetter & A. Th. Erwin, wanted to reconcile this practical system with the sientific system.

But in 1927, they turned the world upside down by defining in their „Systematic study of squashes and pumpkins“: The pumpkins belong to either of two species, Cucurbita pepo or Cucurbita moschata, and the squashes to Cucurbita maxima.

The species Cucurbita maxima from the southern hemishpere should get the name „Squash“ from the northern hemisphere…

Jack O‘ help!

Because they formulated their definition without justification, we will never know why they did it their way…

U. P. Hedrick & W. Th. Tapley denoted this attempt in their „Vegetables of New York, Vol. I, Part IV, The Cucurbits, p. 3, footnotes“ in 1934 as not logical and unsuccessful.

The French did a better job from the start; they called all members of the northern species C. pepo „Citrouille“, the varieties of the species from the middle of the Americas C. moschata „Musquée“ and the varieties of the southern species C. maxima „Potiron“ regardless their usage or other features – but they have to learn the distinctive characters of the different species…

Jack O‘, I don’t know, who kicked you out of the fairytale „Cinderella“. In the original version, you were a Citrouille and transformed into a coach. But today a cousin of you from the far South, a Potiron, is playing your role – and you have to stay outside in cold weather; that’s not fair, I think.

Don’t mind! Have a little bit fun anyway with the following nice motion picture from 1934: „Cinderella Betty Boop“…

In the 8th chapter, I report the current status of the case „Squash vs. Pumpkin“ and express the hope that you are smarter now than before

Today pumpkins have lost the smell of fodder, because they weren’t feed to livestock anymore. So, we can „reshuffle the cards“.

Harry S. Paris, a cucurbit specialist and breeder of market vegetables, reminds us in 2005: The words pumpkin and squash are often used interchangeably; to end this, he proposes a new naming system:

- All round cucurbits, eaten as mature fruit, should be called „Pumpkins“.

- All elongated cucurbit fruit, eaten immature, should be called „Squashes“.

But because we have round squashes (as „Rondini“ or „Tondo di Nizza“), we need more classification (new trading classes) in squashes from elongated to round. At the end he comes up with „pumpkin squashes“ for round squashes.

- Pumpkin, Scallop, Acorn, Crookneck, Straightneck, Vegetable Marrow, Cocozelle, Zucchini

- …all summer squashes…

- …become winter squashes

Dear Pumpkin Jack O’Lantern, isn’t that too much for your little brain?

At the end the clarification will be this: In the USA, all immature cucurbits used for eating (by humans) are called „Summer Squashes“; all mature eaten cucurbits are called „Winter Squashes“. All cucurbits used for other purposes, e. g. for a lantern, are called „Pumpkins“.

In the last chapter, I share my ideas on why pumpkins and Jack O’lanterns are orange

I promise this is the last chapter!

Only briefly I will complete the attempts of defining „Squash“ and „Pumpkin“ with the classification sheme of the Great Pumpkin Commonwealth’s (GPC) (cultivates the hobby of growing giant pumpkins throughout the world) which depends on color: Squash will be classified as follows- 100% of the following colors or color combinations: green, blue, and gray. […] Pumpkins will be all fruit not classified as squash.

- Laughing pumpkin

- Jack-o‘-Lantern on a Cafe table in Berlin

- No squash, Pumpkinhead! But I love you all!

The GPC doesn’t use the word „orange“.

But I want to tell you why pumpkins and Jack O’lanterns are yellow-red (the color combination which is called „orange“):

The Manitous, the red man’s spirits, once came over the white-skinned people and made them prefering the color „Yellow-red“ for pumpkins without knowing, why.

The reason is, on Hallowe’en, the Manitous want the white man to honor the native people who had found the edible cucurbits and had tended them for millennia. The Indigenous of the Americas are the hallows, Jack O‘! You know, but the white man doesn’t know…